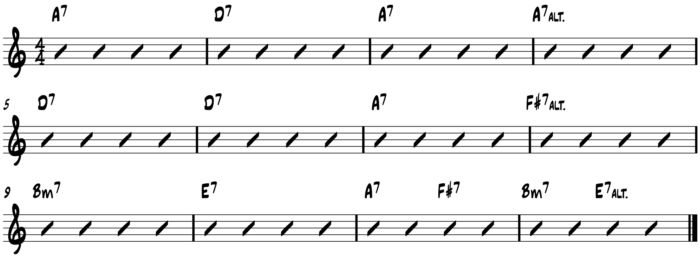

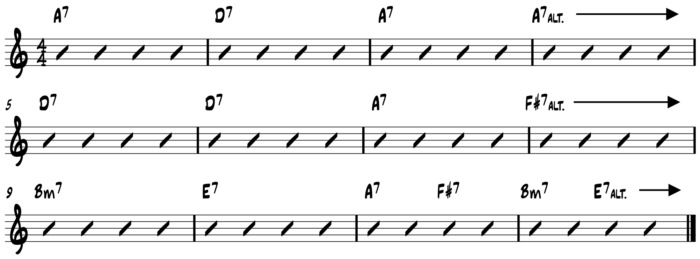

One of the things that distinguishes the way most jazz musicians play the blues from the way most blues musicians do is the way the jazz musicians approach the end of each four-bar line of the blues form. For starters, the jazz version of the blues form usually includes a few extra chord changes, so the whole twelve bars end up looking like this:

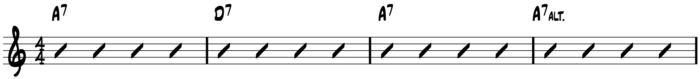

It’s easier to get a handle on if you look at things line by line. So, in the first four bars, we’re just adding in a A7alt. chord in bar four:

“Alt.” stands for “altered;” an altered chord is a dominant seventh chord with any of the weird notes added on top: the b13, the b9 or the #9. We’ll get to why you’d add them in just a moment.

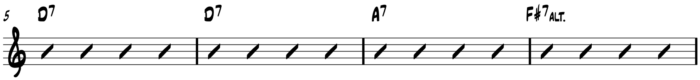

In the second line, we’ve now got a F#7alt chord in bar 9. F#7alt is the VI chord in the key of A and the secondary dominant of the upcoming Bmin chord in measure 9:

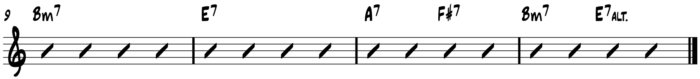

Finally, in the third line, we’ve got the aforementioned Bmin7, the ii in the key of A, followed by the V we’d expect, E7. Then, in the last two measures, it’s like we’ve taken measures 7 through 10 and compressed them, so they go by twice as fast – A7, F#7, Bm7 and E7, or I, VI, ii, V:

So what are these chords doing there, and why are most of them altered? If you look again, you’ll see that all of the altered action is happening at the end of a line. In fact, now all three lines of the form end with an altered chord. What’s more, each altered chord is the V chord of the change that begins the next line. So the A7alt in measure 4 is the V of the D7 in measure 5, the F#7alt is the V of the Bmin in measure 9, and the E7alt is the V of the A7 that would begin the next chorus of the form:

There’s more to altered chords than I’m going to explain here, but I’ve always found it easiest to think of them as “extra-dominant” chords. Dominant chords are supposed to be the chords to take you elsewhere the most convincingly, but since nearly every chord on the blues is already dominant, an altered dominant chord gives you the added tension necessary to resolve to yet another (un-altered) dominant chord. That tension comes from the altered chord’s “altered tones” – the b13th, b9 or #9 that have been “altered” or raised/lowered a half step from the natural 13th or 9th that should occur diatonically in the chord.

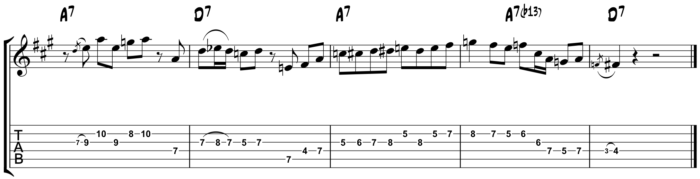

Right. So what good is it, knowing all this? Well, if you’re hip to where to alter the chords on the blues, you can then create melodic lines when you improvise that reflect those altered changes. The lick below is an example of just such an approach. For the first two bars, it’s just blues licks in A. In measure three, we climb up chromatically from the root to the b7, and then in measure 4, we work back down to the F natural, or b13 of A7 and descend through the 3rd, root and b7 of an A7 arpeggio before resolving to the F#, or the third of D7, at the start of measure 5.